In the News

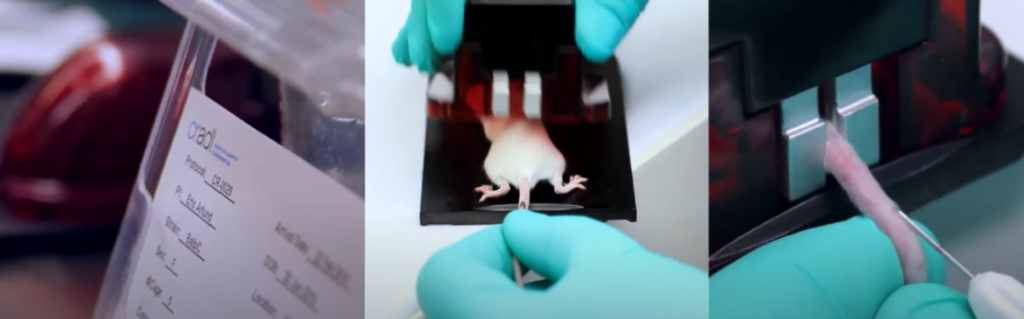

Preclinical Imaging RFID Tag Shaped by Research-Compatible, Digitail

Imaging studies play a pivotal role in the drug development process, helping scientists visualise physiological and metabolic responses to disease and treatment, and guiding promising candidates toward clinical trials. Accurate identification of laboratory rodents is essential for precise tracking, monitoring, and data collection during preclinical imaging.

Traditional animal identification methods often struggled to integrate seamlessly with imaging workflows, until the introduction of Digitail, the world’s smallest RFID Tag, designed with the ideal size, material composition, and durability for preclinical imaging studies.

Types of Preclinical Imaging

Imaging techniques in the preclinical research sector, today, boast an expansive and innovative approach to drug discovery applications. After the introduction of the X-rays, by Wilhelm Conrad Roentgen in 1895, the properties of this new type of radiation (which was able to go through materials of notable thickness) were taken and developed to form various radiograph techniques.

Today, preclinical imaging offers a variety of methods to study disease biology and the anatomical and physiological responses to potential treatments. These include:

MRI

One of the most widely recognised preclinical imaging tools is magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which uses magnets and radio waves to visualise detailed internal structures. Despite its precision, MRI is among the most costly imaging techniques and often has a longer turnaround time.

While it is used in certain preclinical studies, it may not be the most effective choice when high temporal resolution is required.

CT

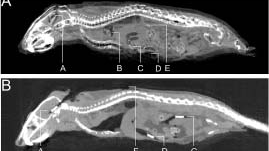

Computed tomography (CT) uses Roentgen’s X-rays to generate detailed cross-sectional images of bones, tissues, and organs, often with a rapid turnaround.

While highly effective for structural visualisation, its use in longitudinal preclinical studies is limited because of exposure to ionising radiation.

PET

Preclinical PET imaging, or positron emission tomography (PET), is an alternative tomography method that uses tracer liquids to visualise metabolic and molecular-level processes. This technique provides valuable insights into disease mechanisms and treatment responses at a cellular level in preclinical research.

Although PET imaging requires specialised equipment and tracers, it provides the most precise quantitative assessment of molecular targets, making it invaluable for detailed preclinical research studies.

Ensuring Accurate Tracking in Preclinical Imaging with RFID Tags

Each modality of preclinical imaging has its pros and cons, and the method chosen typically depends on the research goals, molecular targets, and study requirements. New and innovative imaging techniques continue to expand our understanding of complex biological processes. For example, bioluminescence imaging has proven highly sensitive for tracking gene expression, cell migration, and tumour growth in vivo.

Regardless of the imaging modality used in preclinical research, the accurate identification of laboratory rodents within any study cohort regardless of length or volume is essential.

Using a preclinical imaging RFID tag ensures each animal has a unique identifier, allowing specific biological data to be linked with behavioural insights. This connection between imaging results, behavioural observations, and individual study rodents enables traceable, efficient, and error‑free research outcomes.

What is the purpose of preclinical imaging?

The Role of Preclinical Imaging and RFID Tags in Research

Understanding the purpose of preclinical imaging is essential when selecting a compatible identification method, such as a preclinical imaging RFID tag. These imaging modalities are often part of research programs aimed at studying disease progression, also known as disease modelling. By imaging laboratory mice and rats, researchers can track how a disease develops within the body and translate these insights into clinical applications.

Imaging studies also provide valuable cognitive data that support understanding of brain function, which is pivotal for medical advancements. When combined with behavioural studies, preclinical imaging can assess the effects of genetic modifications, therapeutics, and other interventions on brain activity and behaviour.

Beyond disease modelling and cognitive research, preclinical imaging is widely used to evaluate the safety and efficacy of new therapeutics, drug candidates, and vaccines. This makes imaging a vital tool not only for understanding disease and motor function but also for assessing treatment outcomes and advancing global health initiatives.

Radio frequency identification is the ideal method for imaging identification

Radio frequency identification (RFID) is often the most suitable method for animal identification in preclinical imaging, as it meets the high standards of compliance, accuracy, ethical practice, and efficiency required in research.

Research facilities, including hospitals and universities, are governed by strict animal welfare guidelines. In the UK, for example, every preclinical study must justify laboratory rodent usage to the relevant regulatory body, adhering to the Three Rs principles of Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement.

Using non-invasive preclinical imaging RFID tags minimises discomfort and stress for research subjects compared with traditional methods such as ear tags or notching. RFID technology also supports streamlined data collection, high-throughput studies, automation, and seamless integration of imaging data.

Because many preclinical imaging modalities are employed in longitudinal studies, RFID tags are particularly valuable for long-term tracking. They allow researchers to monitor physiological changes, disease progression, and treatment effects across extended study periods with accuracy and reliability.

Why Some RFID Tags Are Unsuitable for Preclinical Imaging

A key challenge for imaging research scientists and radiochemists is that many commercially available RFID tags are not specifically designed for laboratory rodent use. Traditional glass transponders, for example, often face limitations in preclinical imaging studies. This lack of compatibility can hinder certain research programs and create issues such as:

Materials

Many RFID tags contain metallic components, such as antennas or traces, which can interfere with preclinical imaging modalities particularly MRI and CT causing image distortions.

Tag location and durability

Some RFID tags may migrate after implantation. Migration can not only appear in imaging scans but also reduce image quality. Additionally, tags must withstand repeated handling, sterilisation procedures, and environmental conditions during longitudinal studies. Malfunctions, migration, or degradation over time can compromise research data.

Quality of imaging

Interference from metallic components or improperly designed tags can create distortions, streaks, or voids, reducing the visibility of anatomical structures. This can impair 3D image assessment and slow the progress of studies, including those focused on drug development.

Electromagnetic risks

RFID tags with metallic elements can interact with imaging equipment, causing electromagnetic interference. In severe cases, this may generate heat and potentially affect the welfare of laboratory rodents.

Frequency

Some RFID tags operate at frequencies similar to imaging devices, which can degrade signals. Disrupted communication between the RFID tag and the reader may lead to inaccurate data collection.

Digitail: The Ideal Preclinical Imaging RFID Tag for Research Compatibility

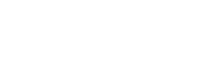

Digitail, Somark’s unique preclinical imaging RFID tag, is specifically designed for use in laboratory research, making it highly compatible with imaging studies and programs. Unlike conventional tags, Digitail contains no ferrous materials, instantly eliminating electromagnetic and frequency interference risks.

At just 16 times smaller than typical glass transponders, the tag is encased in a Parylene C layer, providing a dielectric barrier that protects both the tag and the laboratory rodent from imaging equipment interference.

With numerous IACUC and other ethical approvals, implementing radio frequency identification in preclinical imaging research is straightforward with Digitail.

By addressing the limitations of glass transponders through its intrinsic design, Digitail enables research institutes to benefit from automation, accurate data reads, and seamless system integration without concerns about compatibility with preclinical imaging modalities.